Nikhil PahwaJun 01, 2019 16:00:08 IST

India’s new government was sworn in yesterday. The question we’ve been asked several times over the past few weeks is: what will this government do when it comes to Internet policy? The feeling of uncertainty around Internet policy is not unwarranted, especially given frenetic activity in the space since the beginning of 2018, where many new policy consultations were begun, and at times, orders were sprung upon businesses unexpectedly. Here are the themes or trends, based on what has happened over the past couple of years, that I feel are going to define Internet policy in India going forward:

1. A “Rights, but” approach to policy making

…as opposed to a “Rights first” approach to policy making.

Human rights, and indeed, fundamental rights, are an inconvenient obstacle for the government, and policymaking will give primacy to growth and security objectives over rights.

The whitepaper on data protection, at a time when privacy was a significant concern, seemed to highlight the importance of data for economic growth and AI development, trying to find a balance between privacy and economic imperatives; the data protection bill that followed avoided limiting mass surveillance, while largely excluding the government from restrictive provisions of the bill. So, it became common to hear: “privacy is important, but what about economic growth and national security?” While looking to amend the IT Rules for online platform safe harbor, the line we heard often from the bureaucracy that they don’t want to remove encryption or harm privacy, but they need to mandate traceability. Remember what Ned Stark said in Game of Thrones about the word “but”? Read this.

Commuters watch videos on their mobile phones as they travel in a suburban train. Reuters

Recommendations:

- Civil society and members of the public will have to be prepared to litigate in order to ensure that rights are protected, but also need to ensure that they’re present at all forums, speaking up on every issue, in every consultation. They need to ensure that their voices are heard, and whenever needed, dissent is recorded, if not by the government, then publicly.

- Businesses will have to examine their role in protecting the rights of their customers, and take appropriate action, whether independently, through industry bodies, or supporting rights-based organisations. Let’s not forget that businesses and industry bodies have litigated before: both in favor of retaining Aadhaar and for strengthening safe harbor (Section 79). There might be a need to go to court in order to protect privacy and/or safe harbor.

2. Data as a national asset

…as opposed to an individual right.

Data is the new oil is a phrase we’re hearing often, from ministers, industrialists and regulators. Ensuring that data remains in government control either directly or via Indian corporations, seems to be an area of focus for government policy. Analytical data, previously seen as a company’s intellectual property, is now being deemed ‘community data’, and thus belonging to the Government of India. There are three related sub-themes emerging:

2a. The digitisation of everything: As opposed to the idea in some cybersecurity circles that data is a toxic asset, and the cost of loss of data for an individual far exceeds the value for business of retaining it, the Indian government is in data collection and data generation mode. Whether it is digitisation of government schemes and interactions, or digitisation of public and private activity through the National Health Information Network, the installation of RFID chips on all vehicles, the identification project Aadhaar, or the creation of a public credit registry, India is undergoing an exercise of taking personal information and converting it into a public asset, all linked to a single unique ID number in Aadhaar, which lends itself to public and private profiling of individuals. Thus, the digitisation of everything leads to an increase in data generation, collection, and profiling.

2b. Data localisation: The corollary to the idea that data is a national asset is the idea that a national asset cannot be allowed to leave the physical boundaries of the country. While the data protection bill drafted by the Srikrishna Committee favored data mirroring, the RBI has mandated data localisation for financial transaction data, and the draft e-commerce policy suggested data localisation for e-commerce companies within a period of three years. It wouldn’t be surprising if the final version of the data protection bill will enforce data localisation instead of mirroring.

2c: Data access and sharing: Data, once localised, needs to be available for enabling economic growth. Thus, both the first (leaked) and second (public) draft of the e-commerce policy mentioned the need to share community data with Indian startups. In addition to this, there are various “stacks” being created, whether for financial data, Healthstack for health data, or Dronestack for drone related information. While consent mechanisms will be critical here, along with Aadhaar, these stacks will enable the conversion of personal information first into public assets, and then enable privatisation. Consent may not necessarily be voluntary here, as denial of services has been seen as a means to enabling data collection.

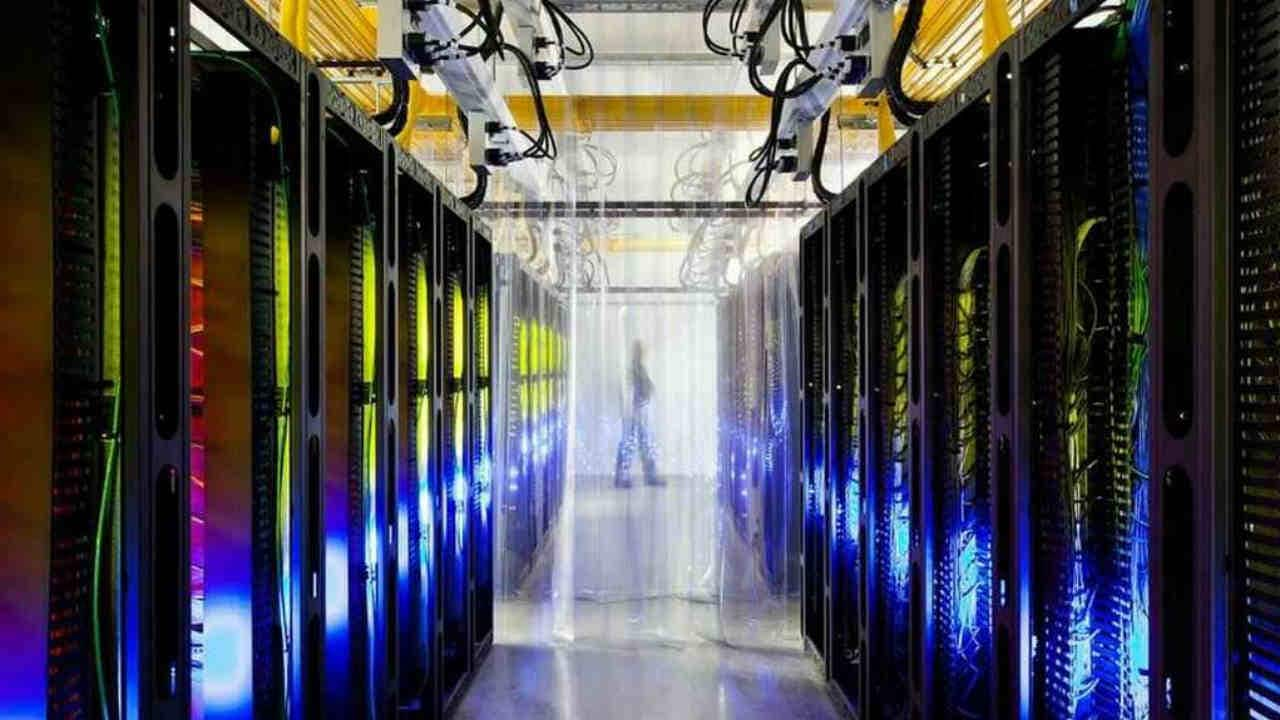

Servers inside a Google data centre. Image: Google

Recommendations:

- The idea of data being the new oil and being a national asset seems to be deeply ingrained in bureaucratic thinking and government action, and this needs to be challenged by ensuring that individual rights are at the center of all discussions. Civil society organisations need to help address key government concerns around competition, network effects and law enforcement, which allow them to push for data localisation. Provide alternative solutions to these issues. Data portability is a probable solution for addressing competition concerns. Civil society organisations also need to ensure that consent is meaningful and limited to a specific purpose. Mass data collection needs to be challenged both from a rights and a security breach perspective, as and when breaches happen; profiling of citizens needs to be challenged from a rights perspective. The real challenge will be addressing unrestricted and disproportionate government access to data.

- Businesses can ensure that meaningful consent and purpose limitations are a competitive force for good, and participate in consultations and regulatory processes to ensure that customer rights are protected. Privacy helps build customer confidence and offers economic growth.

Remember: the code is law. Thus, accountability, neutrality and transparency in operations of various “stacks”, especially in the framing of policies and design of these systems, to allow equal opportunity for all businesses, is in everyone’s interest, and the need for preventing monopolisation, for example in case of NPCI, is essential.

3. National Security as a driving force

Cyber security is now being seen as critical for National Security, and this includes not just protecting critical digital assets and an increase in interception and monitoring of communications, but also protecting citizen data from being sent overseas. This is largely applicable to the activities of foreign players. At a recent TRAI Open House, on a consultation regarding the regulation of OTT communication applications, there was a row of ex-armed forces personnel, some of them high ranking, of the level of a Lt General. They demanded that calling via services like WhatsApp be intercept-able, at one point, alleging that terrorism in Kashmir returned after such apps became popular. We’re seeing National Security concerns being raised even at discussions on data protection, e-commerce, with economic security also being seen as a critical part of policymaking.

Representational image. Pixabay.

Recommendations:

While security is only being looked at from the perspective of law enforcement access to data, the point that backdoors will invariably be misused and are themselves a security concern is an argument that isn’t being made by many. The focus on National Security has shifted focus away from individual safety, and the point that you can’t make the country secure by making all citizens vulnerable is rarely made. At the same time, civil society organisations need to address legitimate government concerns around international misuse of data, by foreign governments, which is used to both justify data localisation and unrestricted law enforcement access to data.

Businesses need to highlight concerns around the security of their customer data and the safety of their customers. Trust in digital services ensures greater usage and freedom in usage.

4. Regulators gonna regulate

There has been a dramatic increase in regulatory activity, especially since early 2018. As more and more people start using the Internet in India, ministries and regulators seem to be under increasing pressure to draw boundaries around what they think is their regulatory turf. Some, like TRAI, appear to be going beyond their jurisdiction of telecom and Internet-access, by looking into privacy, online communications apps and now possibly online video streaming apps with an intent to expand their remit. Others, like the DPIIT has recently encroached on the jurisdiction of MeitY by looking at data protection issues in the draft ecommerce policy.

Un-regulated or even lightly-regulated sectors, companies and activities, whether cryptocurrency trading, online streaming of video and music, online news publications and blogs, ecommerce platforms, mobile wallets, VoIP calling and messaging, social media and even online pharmacies saw much greater regulatory interest and scrutiny over the last year. There almost seems to be a belief that nothing should be allowed to operate unregulated, and freedom to experiment should only be in a controlled and restricted environment, which is a “regulatory sandbox”. Especially in the first quarter of this year, we’ve heard from lawyers, civil society and public policy executives about how stretched they have been, dealing with various issues cropping up, many unexpectedly.

Recommendations:

Increased regulatory activity calls for greater capacity building in policy issues, whether among civil society or industry. It also means that regulators and ministries, given the pressure on them to do something, also need to increase interactions with a wider set of stakeholders, to help build their capacity, given the impact that regulations will have. Regulatory overreach and jurisdiction expansion need to be challenged, lest it continues unopposed.

An employee works on his computer in Bangalore. Image: Reuters

5. Preference for national megacorps

Scale is scary for the Indian government if those large corporations don’t belong to India. Facebook and its mess around privacy and misadventures with Free Basics haven’t helped either. The concern about potential “digital colonisation” is pervasive, even as nationalism replaces the internationalism that liberalisation and the Internet brought in. The idea that data gathering (like the creation of oil reserves) is a strategic national exercise hasn’t just led to the push for the creation of large government datasets: it has also resulted in a strategic move towards strengthening Indian megacorps and weakening large global corps. Indian companies, even if foreign-funded, are using this opportunity to push the nationalist agenda: the politicisation of Indian startup rhetoric began largely with the Startup India conference in January 2016 and has now found its way into regulatory filings and public pronouncements. The China model is being used by Indian businesses to push government policy to favor them and hurt global competitors.

Recommendations:

Strong privacy regulations, and an active data protection authority, as well as a re-look at competition law to address growing concerns around the centralisation of the Internet are necessary, not just to address concentration of power and data with global megacorps, but also Indian megacorps. While larger entities might be easier to regulate, innovation has rarely been the preserve of incumbents on the Internet, and individual freedoms often have been preserved through the infinite competition that the Internet has allowed. It’s important for industry and civil society to push for decentralisation of the Internet, even though this is unlikely to happen, and regulators are likely to support the idea of national oligopolies.

6. Process as an inconvenience in policymaking

The TRAI, despite lack of transparency in final decision-making (wherein dissent, if any, remains private and/or unrecorded), remains the gold standard for policy consultations in India: it often has pre-consultation discussions and papers, issues a consultation paper for comments, gives adequate time for participation, allows for a counter comment stage, while at all times, allowing for comments and counter comments to be public, and there being open house discussions post submissions. In contrast, other departments haven’t been consultative or transparent. The Reserve Bank of India’s dictat to localise digital payments data came out of the blue and involved no public consultation or transparency in decision making. The submissions made to the data protection bill were never made public by the committee, neither were the comments on the bill itself. The data protection bill consultations were hosted without giving adequate time for participants to prepare their responses, and indeed, before even the submission deadline. Submissions to DPIIT on the e-commerce policy are not public, and there have been no open house discussions. In case of changes to the IT Rules, the consultation process seemed to begin almost as an afterthought, after information about rules being amended leaked to the media. Due process is an inconvenience for many departments, and sometimes responses aren’t even available under the Right to Information Act, which itself is under threat of dilution.

Recommendations:

Due process and transparency in policymaking are critical for retaining both public and industry trust. A meaningful and sincerely run process is a necessary (but not sufficient) condition for creating a meaningful outcome. Participation allows all stakeholders, especially citizens, to be heard, and their points noted or taken on record. It is essential for everyone, whether civil society organisations, citizens, the media, or businesses, to push for an open, consultative, fair and transparent process. Lack of due process will eventually impact investment, even though some might continue to throw good money after bad.

This article originally appeared on MediaNama.

Tech2 is now on WhatsApp. For all the buzz on the latest tech and science, sign up for our WhatsApp services. Just go to Tech2.com/Whatsapp and hit the Subscribe button.

Post a Comment