The ConversationApr 20, 2021 15:25:40 IST

Space is getting crowded. More than 100 million tiny pieces of debris are spinning in Earth orbit, along with tens of thousands of bigger chunks and around 3,300 functioning satellites. Large satellite constellations such as Starlink are becoming more common, infuriating astronomers and baffling casual skywatchers. In the coming decade, we may see many more satellites launched than in all of history up to now.

Collisions between objects in orbit are getting harder to avoid. Several technologies for getting space debris out of harm’s way have been proposed, most recently the plan from Australian company Electro Optic Systems (EOS) to use a pair of ground-based lasers to track debris and “nudge” it away from potential collisions or even out of orbit altogether.

Tools like this will be in high demand in coming years. But alongside new technology, we also need to work out the best ways to regulate activity in space and decide who is responsible for what.

Active debris removal

EOS’s laser system is just one of a host of “active debris removal” (ADR) technologies proposed over the past decade. Others involve sails, tentacles, nets, claws, harpoons, magnets and foam.

Outside Australia, Japan-based company Astroscale is currently testing its ELSA system for capturing debris with magnets. The British RemoveDEBRIS project has been experimenting with nets and harpoons. The European Space Agency (ESA) is engaged in various debris-related missions including the ClearSpace-1 “space claw”, designed to grapple a piece of debris and drag it down to a lower orbit where the claw and its captured prey will end their lives in a fiery embrace.

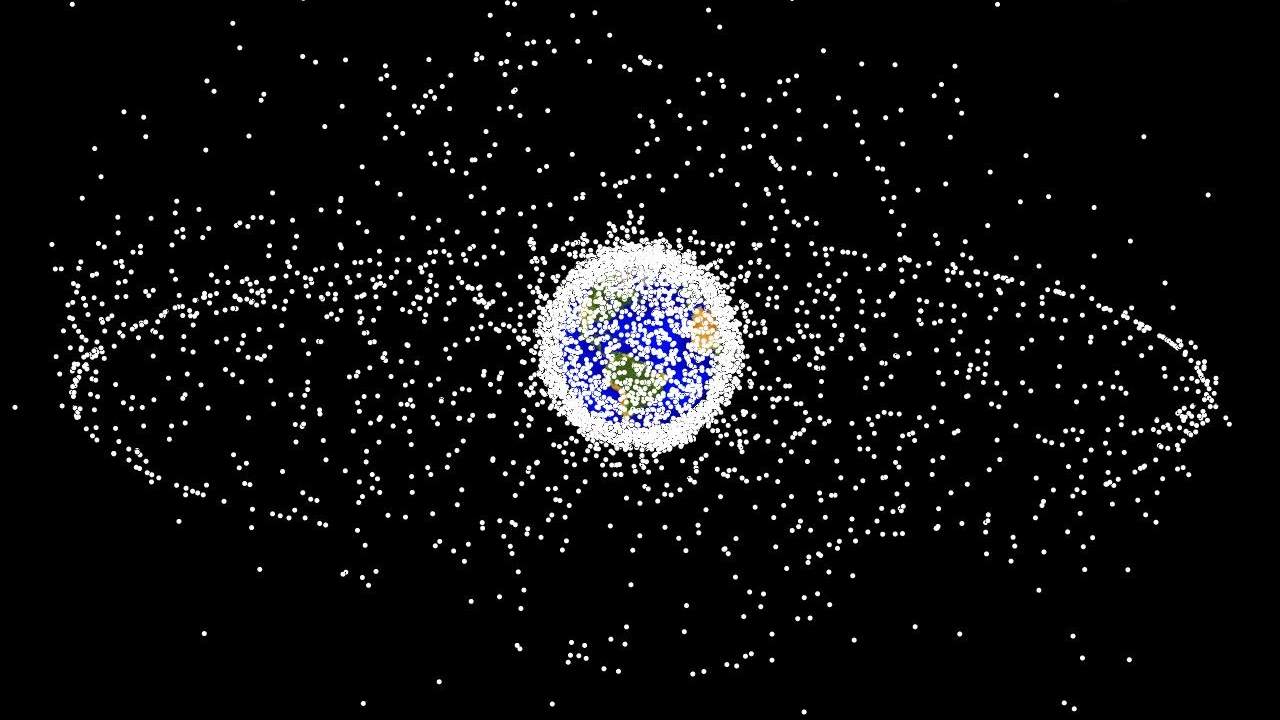

A computer-generated image of objects in Earth orbit that are currently being tracked by the US Air Force. Roughly 95% of the these objects are debris/not-functional satellites. Image credit: NASA

Close calls are becoming more common

Space debris poses a very real threat, and interest in ADR technologies is growing rapidly. The ESA estimates there are currently 128 million pieces of debris smaller than 1cm, about 900,000 pieces of debris 1–10cm in length, and around 34,000 pieces larger than 10cm in Earth orbit.

Given the high speed of objects in space, any collision – with debris or a “live” satellite – could create thousands more pieces of debris. These could create more collisions and more debris, potentially triggering an exponential increase in debris called the “Kessler effect”. Eventually we could see a “debris belt” around Earth, making space less accessible.

In recent times, we have seen several “near collisions” in space. In late January 2020, we all watched helplessly as two much larger “dead” satellites – IRAS and GGSE-4 – passed within metres of each other. NASA often moves the International Space Station when it calculates a higher-than-normal risk of collision with debris.

More satellites, more risk

The problem of space debris is becoming more urgent as more large constellations of small satellites are launched. In 2019, the ESA sent one of its Earth-observing satellites on a small detour to avoid a high possibility of a collision with one of SpaceX’s Starlink satellites.

In just the past few days, satellites from One Web and Starlink came perilously close to a collision. If the well-publicised plans of just a few large corporations come to fruition, the number of objects launched into space over the coming years will dwarf by a factor of up to ten times the total number launched over the six decades since the first human-made object (Sputnik 1) was sent into orbit in 1957.

Space law can help

Any feasible technology to alleviate the problem of space debris should be thoroughly explored. At the same time, actively removing debris raises political and legal problems.

Space is an area beyond national jurisdiction. Like the high seas, space is governed through international law. The 1967 Outer Space Treaty and the four other international treaties that followed set out a framework and key principles to guide responsible behaviour.

While the engineers might envisage nets and harpoons, international law is bad news for aspiring space “pirates”. Any space object or part of a space object, functional or not, remains under the jurisdiction of a “State of registry”.

Under international law, to capture, deflect or interfere with a piece of debris would constitute a “national activity in outer space” – meaning the countries that authorised or agreed to the ADR manoeuvre have an international legal responsibility, even if the action is carried out by a private company. In addition, if something goes wrong (as we know, space is hard), a liability regime applies to the “launching States” under the applicable Treaty, which would include those countries involved in the launch of the ADR vehicle.

The rules of the road

Beyond the legal technicalities, debris removal raises complex policy, geopolitical, economic, and social challenges. Whose responsibility is it to remove debris? Who should pay? What rights do non-spacefaring nations have in discussions? Which debris should be preserved as heritage?

And if a State develops the capability to remove or deflect space debris, how can we be sure they won’t use it to remove or deflect another country’s “live” satellites?

Experts are working to recognise and determine the appropriate regulatory “rules of the road”. The United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS) deals with space governance, and it has had “legal mechanisms relating to space debris mitigation and remediation measures” on its agenda for years. There are already some widely-accepted and practical guidelines for debris mitigation and long-term sustainability of space activities, but each proposed solution brings with it other questions.

In the end, any debris remediation activity will require a negotiated agreement between each of the relevant parties to ensure these legal and other questions are addressed. Eventually, we might see a standardised process emerge, in coordination with an international system of space traffic management.

The future of humanity is inextricably tied to our ability to ensure a viable long-term future for space activities. Developing new debris removal methods, and the legal frameworks to make them usable, are important steps towards finding ways to co-exist with our planet and promote the ongoing safety, security and sustainability of space.![]()

Steven Freeland, Professorial Fellow, Bond University / Emeritus Professor of International Law, Western Sydney University, Western Sydney University and Annie Handmer, PhD candidate, School of History and Philosophy of Science, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Post a Comment