Anirudh RegidiNov 16, 2020 17:32:48 IST

This is the first time in maybe a decade that I’m asking myself this question.

Intel has utterly dominated the desktop CPU space since at least 2006, when its Core 2 architecture launched. And until a few days ago there was no question of opting for anything other than Intel, especially if you were a gamer.

What changed? Everything. And it’s been a long time coming.

It was arch-rival AMD that finally kicked things off. AMD woke up in 2017 and introduced Zen, a completely redesigned CPU architecture that was, by AMD’s standards, superb. Bugs and various optimisation quirks notwithstanding, these CPUs were not good enough to dethrone Intel. In fact, their biggest achievement was shaking Intel out of its complacency, and, I believe, pushing the market beyond dual-core CPUs. But with Intel still at the helm.

With the “world’s fastest gaming CPU” being overthrown in mere months by arch-rival AMD, and Intel’s response prepped for as early as next year, there’s never been a more interesting time to be a PC gamer. Image: Anirudh Regidi

In the middle of this, Intel was dealing with a whole other set of problems. It was struggling to move to a new, more efficient *manufacturing process — a dream that is yet to be realised on desktop, and perhaps won’t be till after 2021. There was also Spectre-Meltdown and a family of related vulnerabilities, mitigations for which were very expensive for Intel to implement, costing Intel CPU users up to 40 percent in performance in some cases.

It’s testament to Intel’s engineering prowess that through all of this, it still delivered. Sure, Intel needed a fire under its proverbial arse to kick things into high gear again, but Intel delivered, and that was all that mattered.

Then came AMD’s Zen 2 in 2019, Intel’s Comet-Lake S about 6 months ago, and finally, AMD’s Zen 3 a few days ago.

Zen 2, on a 7 nm process, brought with it massive architectural improvements for AMD, allowing it to finally be competitive with 9th Gen Intel CPUs. Intel’s response was 10th Gen Comet Lake-S several months later.

Comet Lake-S: An overview

For all intents and purposes, 10th Gen Comet Lake-S is a pretty big jump from 9th Gen. It’s built on the now venerable 14 nm process node (which debuted on desktop five years ago with Skylake), but you suddenly got hyper-threading on all cores across the entire consumer CPU range. The 10600K doubled the thread count over the 9600K, and the 10900K went from 8 cores to 10. Clock speeds improved across the board, and we saw the addition of features such as Thermal Velocity Boost, AI acceleration, and native WiFi6 support.

While I do believe that Comet Lake-S is a placeholder, where Intel simply pushed the basic 9th Gen CPU design to its very limits rather than introduce a whole new architecture, it still worked. Intel kept its lead over AMD — at least in gaming — and these CPUs were, till just a few days ago, the best gaming CPUs you could buy.

There are some drawbacks, though. These CPUs run hot, and they draw a lot of power. And then there’s the fact that you need an entirely new motherboard and that the platform lacks support for the PCIe Gen 4 standard (necessary for modern SSDs and GPUs).

Comet Lake-S performance

The Core i5-10600K and Core i9-10900K, while officially rated at 95 W and 125 W TDP respectively, can easily – with a press of a button, in some cases – hit TDPs of 200 W and 300 W respectively. In this case, TDP or “Thermal Design Power” is essentially the amount of heat that needs to be dissipated to keep the CPU from overheating. If your CPU cooler can’t dissipate enough heat, your CPU will slow down to compensate.

I mean, you could run these CPUs at their rated TDP and you really wouldn’t need anything more than a decently-priced air cooler to do this, but you’d also be denying these CPUs a chance to really stretch their legs.

In my own testing, the 10900K went from a 3.7 GHz base clock to 4.9 GHz (a 33 percent boost) with minimal effort. That’s 4.9 GHz on all 10 cores, by the way, which is huge. For reference, my first-gen 14 nm Intel desktop CPU, the quad-core 6700K, could only hit 4.6 GHz on all cores (~15 percent boost) before I had to push voltages to worrying levels. And this is after hours of testing and tweaking.

The 10600K was almost as good, hitting 4.8 GHz on its 6 cores (~17 percent boost) with minimal effort. With more time to tweak, and better cooling, I think I could have easily pushed both CPUs past the 5 GHz mark.

I would like to point out, however, that the cooling system for this ridiculous overclock cost me Rs 15,000 (I was using the NZXT Kraken x53 AiO liquid cooler), and for the 10900K, it still wasn’t enough. With better cooling, I’m quite certain I could have pushed the CPU even harder.

Was it worth it? Of course, it was!

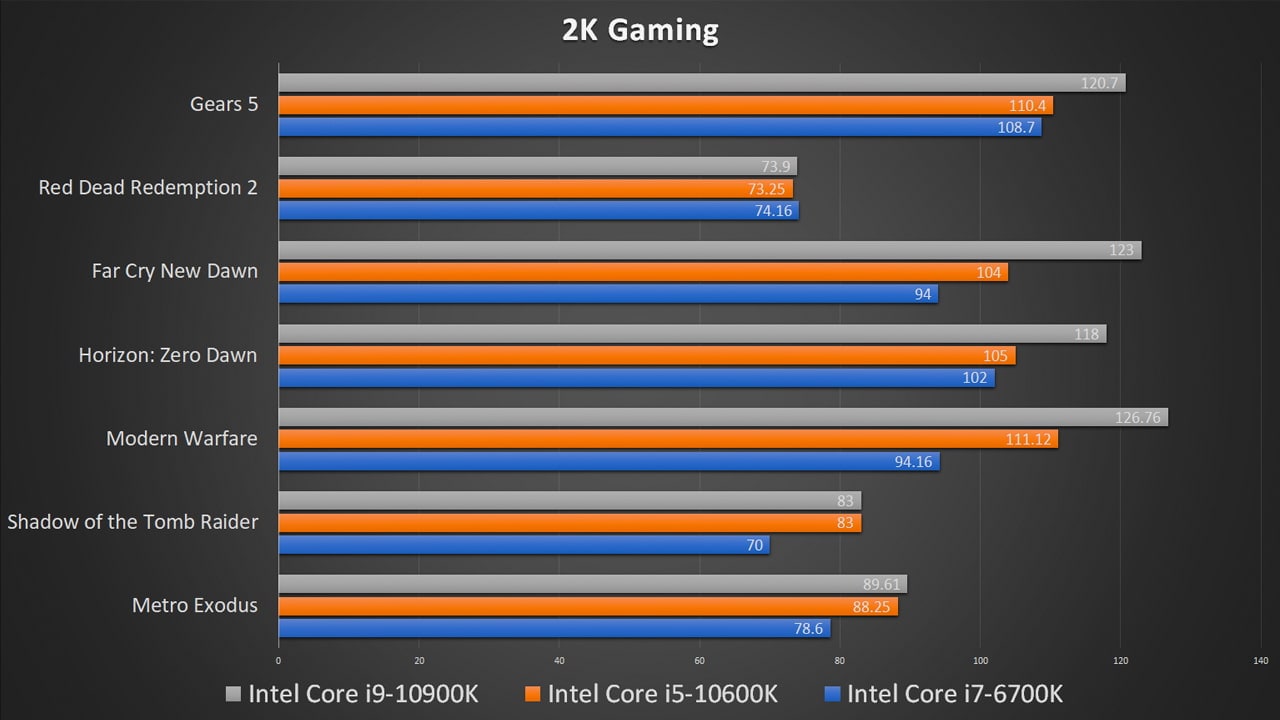

Paired with an Nvidia RTX 3080 from Zotac, a Corsair MP600 SSD, and an ASUS Maximus XII ROG motherboard, I was easily hitting 80+ fps at 2K at Ultra settings with RTX turned on in some of the most demanding games available today. Games like Modern Warfare and Gears 5 breezed past the 120 fps mark.

Depending on the games you’re playing, the performance can go up from ‘barely noticeable’ to ‘I need a faster monitor.’ Still, a GPU upgrade will have a more significant impact than a CPU upgrade.

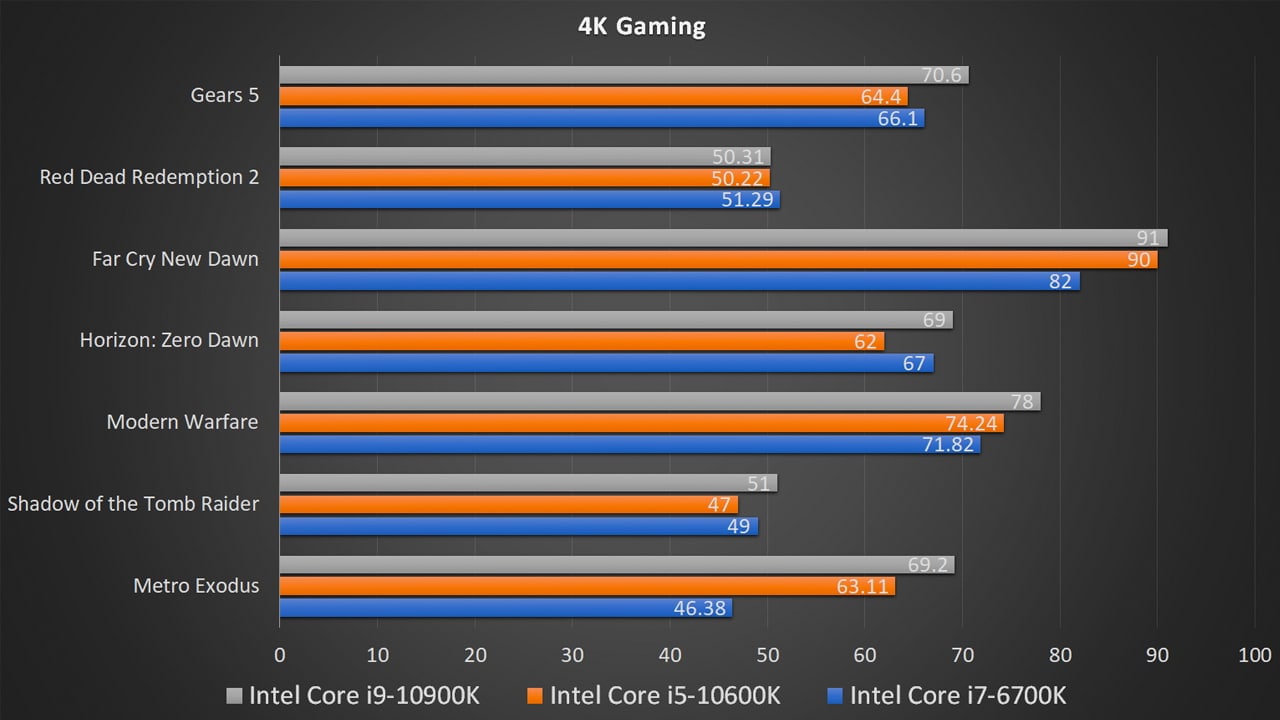

At 4K, the gap closes, with games being so severely bottlenecked that your GPU will slow you down a lot more than your CPU will. As strange as it sounds, it’s OK to not get the fastest CPU for 4K gaming. Get a 3090 instead.

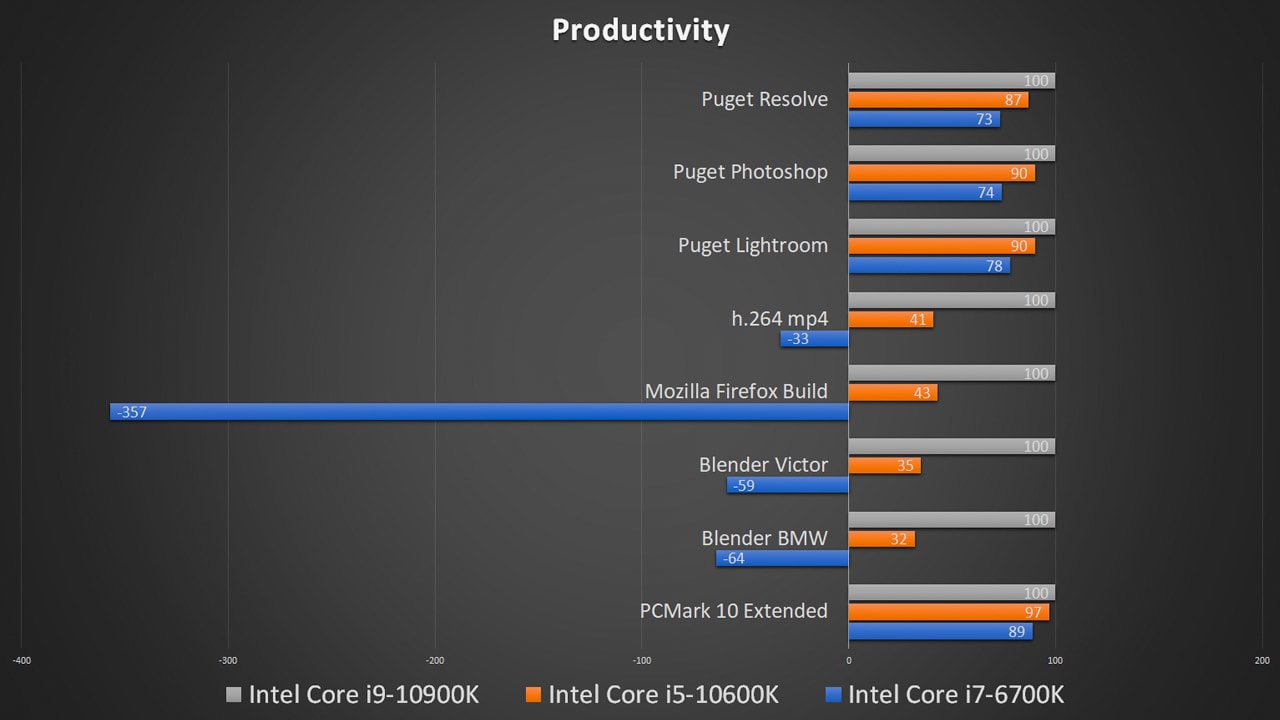

In productivity tests, performance continued to be superlative, with the Core i9-10900K even sneaking ahead of AMD’s 16-core behemoth, the 3950x, in Photoshop and Lightroom benchmarks.

3D renderings were completed in minutes, and 90-minute video clips were converted to H.264 in under 15 min (on the 10900K).

This is also where things start to fall apart.

If we take the 10900K as the baseline for productivity, the gains vs the original high-end 14 nm Intel CPU are phenomenal. Even the 10600K, as capable as it is, can’t compete with the 8 additional threads of processing power that the 10900K can bring to bear. AMD’s 16-core monsters will beat the 10900K, however.

The 10900K is a beast, but in gaming, the 10600K almost matches it, and perhaps could match it with a more significant overclock. In many productivity tests, the GPU has a far greater impact than the CPU. Take Blender, for example, where the Victor test scene took over 12 minutes to render on the 10900K at 4.9 GHz, or 10 times faster than my ageing 6700K.

This would have been impressive, if it wasn’t for the fact that the RTX 3080 GPU managed the same render in 1.5 minutes. The cheaper RTX 2070 Super managed the render in 2.

The 10900K did take a small lead over even the GPUs in video conversion tests, converting a 90 minute 1080p clip to H.264 in 13.5 minutes – vs the 25 minutes it took the 10600K, but the RTX 2070 Super could manage the same in 15 minutes, rendering the capabilities of the 10-core CPU moot.

Clearly, the 10600K is the more sensible option for the bulk of users, and a more powerful GPU can be a lot more useful. But that’s not the end of the story.

If you’re on an older CPU platform — whether AMD or Intel — it still makes more sense to put money into a more powerful GPU before considering an upgrade to Comet Lake-S. The difference in gaming performance between an overclocked 10600K and a five-year old 6700K is just a handful of percentage points at 2K (with one exception), and nearly insignificant at 4K.

Then there’s the fact that you can’t just buy a new CPU and slot it into your existing board. Comet Lake-S demands a new motherboard, which can cost upwards of 13k for something that supports overclocking. Additionally, you also have to account for an expensive cooling solution, which can also cost at least 10k for something that’s powerful enough for a 10600K.

And then, finally, there’s Zen 3

I haven’t had a chance to test the Zen 3-based AMD Ryzen 5000 series CPUs, but there’s enough data available online (stay tuned for a full review of our own) to suggest that Zen 3 is faster than, or at least just as fast as, Intel’s best. It’s also a more mature platform that’s backwards-compatible with older AMD motherboards, supports PCIe Gen 4, and generates a lot less heat (65 W to Intel’s 95 W). This means you don’t need as beefy a cooler for the same level of performance.

If that wasn’t bad enough, Intel’s Rocket Lake desktop CPUs are scheduled for launch in just a few months. While these will still be built on a 14 nm process, Rocket Lake promises PCIe Gen 4 support, additional PCIe lanes, fewer but faster cores, and a brand-new integrated GPU.

Do you still think it’s worth buying an Intel CPU in 2020? I certainly don’t. In fact, if you can hold off on the upgrade for a bit, hold off. Let AMD and Intel slug it out over the next few months. As the data shows, the CPU isn’t that critical to gaming anyway.

Once the dust settles, pick a side and move on. Competition has given us choices.

*The manufacturing process node is a rather complicated definition that usually refers to the size of the smallest feature on a microchip – a CPU in this case. Theoretically, the smaller the process, the more efficient the design. Smaller transistors means lower heat, greater thermal and power efficiency, and by extension, higher clock speeds and more efficient processing.

On paper, AMD’s 7 nm process is twice as good as Intel’s 14 nm. In practice, the waters are a lot muddier, and there’s no clear-cut winner here. Both nodes perform similarly, with Intel’s 14 nm+++ node taking the edge in some cases and AMD’s 7 nm in others.

Ultimately, it’s the architectural design that has a greater impact on performance.

**All tests were conducted on the following test rig:

CPU: Intel Core i7-6700K, Intel Core i5-10600K, Intel Core i9-10900K

Motherboard: Gigabyte Z170-D3H for Skylake, ASUS ROG Maximus XII Extreme for Comet Lake-S

RAM: 2x 8 GB DDR4 3,200 MHz CL15 RAM, courtesy of Corsair

GPU: Nvidia GeForce RTX 3080, courtesy of Zotac

PSU: Corsair AX850 Titanium

SSD: Corsair MP600 1 TB PCIe x4 Gen 4, Samsung 870 QVO SATA 6

Cooling: NZXT Kraken x53 AiO, Artic MX-4 thermal paste

Cabinet: CoolerMaster MasterBox 511 A-RGB in a positive pressure config

Monitor: BenQ EX2780Q

Post a Comment