In late February, I fell ill with a fever and a cough. As a biochemist who teaches a class on viruses, I’d been tracking the outbreak of COVID-19 in China. Inevitably I wondered: Did I have COVID-19, or did I have the flu?

At the time, COVID-19 testing was very restricted but I knew I could get quickly tested for the flu. I drove myself to an urgent care clinic, the nurse easily checked my temperature and took a throat swab and 30 minutes later I got the results: positive for influenza.

The flu test I took is a type of viral screening called a rapid antigen test that looks for viral proteins. For the flu, these antigen tests are easy to administer, decently accurate and give results almost immediately.

Widespread testing for SARS–CoV–2, the virus that causes COVID-19, is critical to knowing if, when and how people can start to return to their normal lives. An antigen test for the coronavirus could be a huge help in expanding testing.

On May 9, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the first antigen test for emergency use in the U.S. These tests are starting to be available across the country and could dramatically change the COVID-19 testing landscape when they become widely available.

What is an antigen?

The human immune system, and in fact the immune systems of most vertebrates, work on a simple idea: Any protein in your body that isn’t encoded by your own genes is probably from a pathogen and should be captured and destroyed.

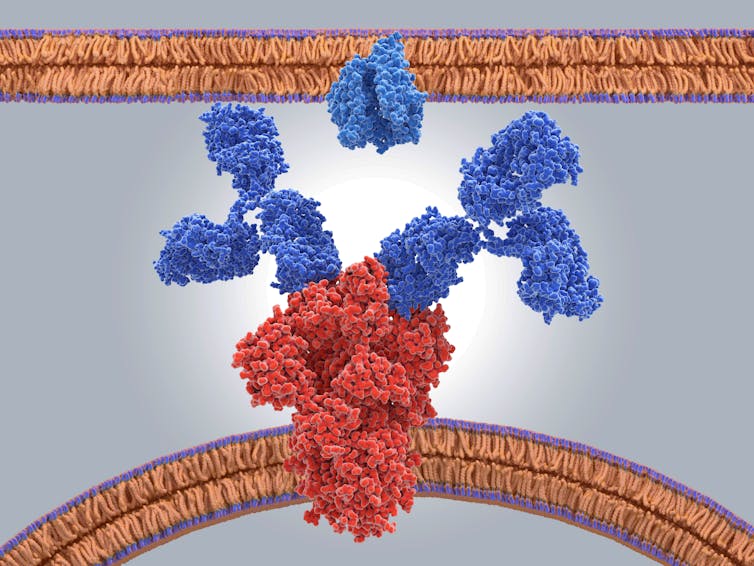

When the immune system detects a foreign protein, your white blood cells, specifically your B-cells, create antibodies to trap and destroy these proteins. Antibodies are Y-shaped proteins that use their arms as grabbers for foreign proteins. The first round of antibodies aren’t particularly well matched to the shape of a new invading protein, but every time white blood cells make new antibodies, they tweak the shape of the antibody grabber until it fits the protein very well.

The foreign protein that triggers this process is referred to as an “anti–gen” because it is an antibody generator.

How does an antigen test work?

Antigen tests are well named: They look for antigens. To identify these antigens, antigen tests use antibodies.

You may have performed one yourself if you’ve ever used a home pregnancy test, which uses tests for an antigen called human chorionic gonadotropin in urine that is produced by the cells that surround a fetus when a woman becomes pregnant.

Like the test that diagnoses influenza, the SARS–CoV–2 antigen test uses antibodies that are produced in animals to hunt for proteins embedded in the coronavirus’s surface. If the antibodies detect viral proteins in a sample, the person most likely has the coronavirus.

An antigen test for SARS-CoV-2 starts with a medical professional collecting a sample of mucus from the back of a persons throat or nose using a swab. They then dip the swab into a liquid to dissolve the mucus and release the virus.

The liquid is then applied to the surface of the test slide that is coated with antibodies. These antibodies are stuck to the slide and “grab onto” any coronavirus proteins that are in the sample.

A second mixture of antibodies is then applied to the slide. These antibodies have been chemically modified with a dye that makes them visible to the naked eye or detectable by fluorescent light.

If the sample contains viral antigen proteins, those antigens are now sandwiched by two antibodies: one that attaches them to the test kit and another that makes them visible. The more coronavirus antigen there is, the more dye will be visible, indicating that the patient is infected with SARS-CoV-2.

If there is no detectable dye, this would mean the person does not have SARS-CoV-2 or that the sample did not have enough viral proteins.

What are the strengths of antigen tests?

The main selling points of antigen tests are that they are far faster and easier to perform than reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests. PCR tests – the swab tests that look for viral RNA – are currently the most common way to test for an active SARS-CoV-2 infection and can take up to four days to perform.

By contrast, the most time-consuming part of the antigen test process is waiting for the antibody mixtures and the sample to mix completely. This process takes mere minutes, given the small volumes typically used in an antigen test. A COVID-19 antigen test might take only 15-30 minutes to complete and requires very little expertise.

Similar tests are done routinely in clinics for influenza all the time. In contrast, PCR tests swabs must be sent to diagnostic laboratories to be performed by experienced technicians as of right now.

What are the weaknesses?

What antigen tests gain in speed and ease of use, they lose in accuracy.

Because they look directly for evidence of the virus, there need to be a lot virus proteins available to stick to the antibodies to produce a detectable result. Depending on the virus, qualitative antigen tests likely need a sample to contain many thousands of viral proteins in order to produce a positive test. If a sample doesn’t have enough virus or a person has a low-grade infection, the test might give a false negative result – and a sick person would get told they are uninfected.

The Food and Drug Administration granted emergency use authorization to a SARS–CoV–2 antigen test made by the pharmaceutical company Quidel Corporation. Quidel reports that their antigen test produces about a 20% false negative rate. That means that 1 in 5 people who actually are infected will receive a result saying they are not. At a large scale, this may result in missing many infected individuals.

Can I get one?

The Quidel test is not currently widely available due to production capacity. As production ramps up and other companies begin to produce antigen tests, they will become more available. Once laboratories around the country begin processing the antigen tests, public health officials will also get a better sense of the real-world false negative rate.

A COVID-19 antigen test can fill an important gap in the testing landscape by providing fast diagnoses in the clinic, but they’re not perfect. Because of the somewhat high false negative rate, individual patients should be careful with how they interpret the results. But when combined with more accurate PCR tests and blood tests that look for antibodies, antigen testing has a large role to play in helping public health officials better understand and fight the spread of the coronavirus.

[Understand new developments in science, health and technology, each week. Subscribe to The Conversation’s new science newsletter.]

Post a Comment