Belgian Paralympic athlete Marieke Vervoort revealed two years ago that in 2008, she had been approved to receive euthanasia. The Paralympian was an accomplished wheelchair racer, having won gold and silver at the London 2012 Paralympics, and silver and bronze at the 2016 Rio Games. However, she suffered from an incurable degenerative muscle disease that caused constant pain, seizures, and in Vervoort’s case, paralysis in her legs. In October 2019, Vervoort made the decision to end her life through euthanasia at the age of 40.

Euthanasia remains a controversial medical procedure. Euthanasia is when a person makes a conscious decision to die, and asks for help in doing so. This might be receiving a doctor or other person to help them. It’s different from assisted suicide, where someone assists an person in taking their own life but the final deed is still done by the individual.

While some proponents, like Vervoort, argue that it can ease suffering, and give a person agency over their own life, others argue that euthanasia is unnatural, and is difficult to properly control – especially in the case of patients who might not be able to fully consent.

Euthanasia has been legal in Belgium since 2002. However, it’s still currently only legal in a handful of countries, including the Netherlands, Luxembourg, and Canada. Although Vervoort felt euthanasia gave her agency over her own life – especially as her condition worsened – her death still highlights many aspects of the moral and legal questions that need to be answered when it comes to euthanasia. Much of the current debate still taking place wonders whether anyone should be able to access it, under what circumstances, and the extent to which we should honour the individual’s choice.

Having the right conversations

My research sought to provide insight into how we can frame our conversations around euthanasia, through speculative design. The field of design is often described as a problem-solving activity. However, many problems are often simply too complex to be solved. The field of speculative design is unique – it’s a method of designing that uses hypothetical prototypes or scenarios to highlight problems rather than solve them. Speculative designs can help consider any potential unintended consequences in a proposed scenario.

I sought to address the complicated moral dilemma of euthanasia by creating The Plug, an applied thought experiment which aimed to think through the consequences of patient control in euthanasia for dementia.

Some terminal conditions, such as dementia, pose more complications for euthanasia. For example, in the Netherlands, an increasing number of people are opting to use euthanasia after being diagnosed with dementia. An advance euthanasia directive is a document in which a person outlines what decisions should be made in the future, should they be unable to make those decision themselves. Currently, many advance directives make statements such as, “when I am no longer myself,” or “when I can’t recognise my children”, to outline when euthanasia should be administered. However, these conditions are hard to measure and comply with.

These advance euthanasia directives are also largely ignored by physicians having to perform euthanasia, because the symptoms of dementia clash with due care criteria – the criteria that a patient must fulfil in order to be administered euthanasia.

Read more: If assisted dying is legalised, who gets to decide whose life is worth living?

In the Netherlands, one study found that only 3% of advance directives are complied with. A person with dementia is often unable to consent at the time of death, which makes it difficult to establish whether the person’s suffering is “hopeless and unbearable” – one of the due care criteria for euthanasia in the Netherlands.

A hypothetical implant

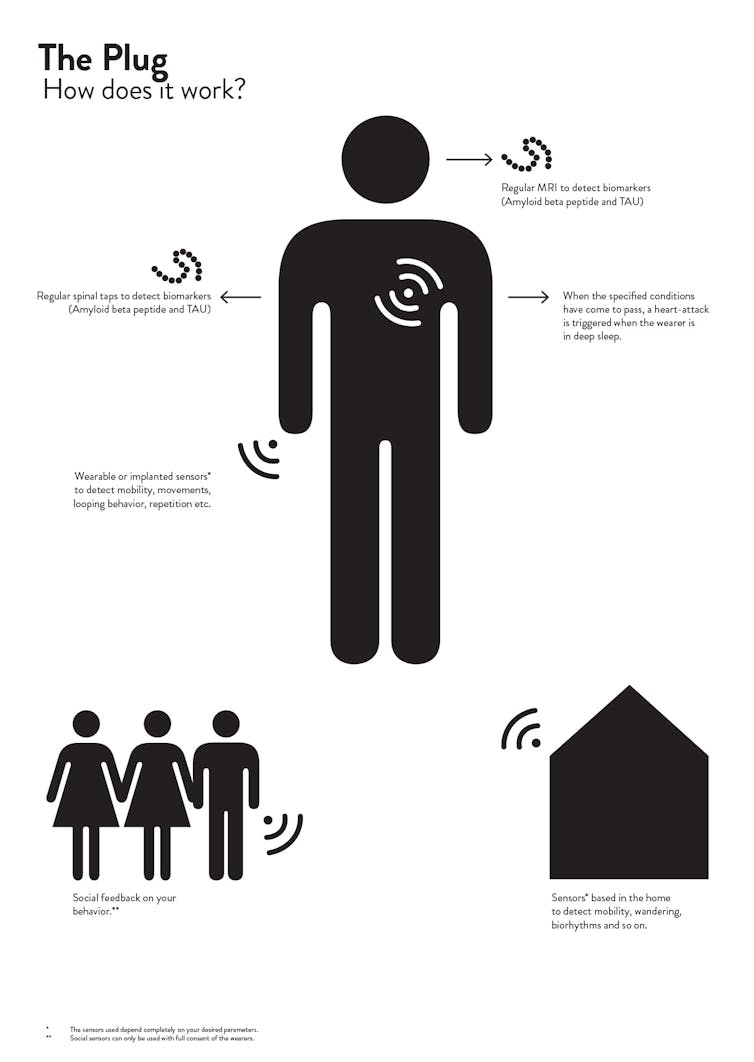

The Plug is a hypothetical implanted advance euthanasia directive that would trigger a swift and painless death once the conditions described in the advance euthanasia directive are reached. My research was intended to address several issues, such as the rights of a person whose personality might be changed because of dementia, the need for advance directives to be much more detailed, as well as the difficulty that physicians may face when performing euthanasia.

The Plug would deal with the consent issue by creating a situation where the person requesting euthanasia is the one who consents. The person they might become as a result of dementia is deliberately excluded in this scenario in order to address who should have the right to decide – the person before dementia, or during dementia.

The Plug would hypothetically be installed in cognitively competent people who might be afraid of developing and living with dementia. The device would be connected to other health-trackers and sensors installed in the home – and potentially even loved ones – to measure if the pre-programmed conditions the patient wants to avoid are coming to pass. If this was the case, The Plug would be triggered, causing the person to die peacefully in their sleep. This scenario was designed to ask a number of questions about advanced euthanasia directives, including how conditions can be measured, and, if they can’t, what decision should be made – and whether it still should.

The applied thought experiment of The Plug has encouraged much conversation among expert stakeholders. It raised awareness about the need for advance directives to be much more specific. Additionally it highlighted the need to acknowledge the contrast in the rights of a person before and after living with dementia. The role of general practitioners was seen as very important, and it is recommended that these doctors initiate end-of-life conversations early, both with the patient and their loved-ones. In places where euthanasia becomes legal, GPs may need additional support or education in order to be able to do this well.

In order to die with dignity, people are increasingly planning their own death. But dementia complicates matters. A person requesting euthanasia must be suffering intolerably and must be able to confirm the request at time of death. However, in many cases with dementia, that “wish” can no longer be confirmed when the time comes. As debates around euthanasia continue, it’s important to consider all the inherent moral dilemmas that come with it.

Post a Comment