Partha P ChakrabarttyJun 06, 2019 21:07:04 IST

This article is the second part of a four-part series which discusses the various nuances involved in becoming an audiophile. You can click here to read part 1.

In the previous article, we discussed the pleasures of audiophilia and the long chain of intermediaries involved in delivering this pleasure to us. We also noted how headphones are the most convenient way to get into audiophilia, and can often deliver great results without breaking the bank. In the next article, we will discuss the various types of headphones, and which ones deliver the most pleasure when we concentrate on the sound. But first, let us take a look at how we can pick the right music files to listen to. In particular, we will focus on the great recordings of Indian music, as you can more easily find details about western music on other websites.

(Once you have quality speakers or headphones, you can return to this piece and listen to the tracks as you read: most of the tracks below are available to stream on Gaana.com. While streaming can vary in quality, their “HD” (320 kbps) option is enough to hear the differences I describe below. HD is only available to Gaana+ subscribers.)

The first step is the quality of the recording. For this, we have to be aware of studios that do an exceptionally good job when it comes to producing music. While most top-tier studios in the West are reliable, things get a little more complicated when we think about Indian music, particularly older music from Bollywood’s golden age.

Representative Image.

Gems from Bollywood’s illustrious history

Bollywood from the 50s to the 80s was miraculous both musically and lyrically. It featured the genius of SD and RD Burman, Roshan, Naushad, Hemant Kumar, Madan Mohan and Salil Chowdhury, just to name a few; and they had iconic voices in Rafi, Kishore, Lata and Asha to give life to their compositions. Then there were the lyrics of Shailendra, Sahir, Kaifi, Majrooh and the early Gulzar. The pleasures of this music are not tarnished by the poor quality of recordings, but that the recordings were poor is undeniable.

O.P. Nayyar’s Taarif Karoon Kya Uski (1964), in its CD version released by Saregama, has Rafi’s silken voice fluctuating arbitrarily in volume, with the guitar riff at the start and the sitar interlude coming in at 1:51 sounding rough and raspy. The delightful castanets used throughout the track — castanets came to Bollywood from Spain — also feel ‘recessed’, or lost in the background. (For a lovely introduction to the range of instruments used in Bollywood music, something you’ll find yourself getting curious about as you become an audiophile, refer to Mrandmrs55.com’s guide.) The tragedy of the loss becomes clear when we listen to the sitar intro in The Beatles’s Norwegian Wood, recorded at EMI Studios and released in 1965. If only the same audio recording technology had found its way to India!

The faces of the four Beatles appear on the fabric of a shirt. Reuters

Vocals get better by the 70s, with RD Burman’s Chura Liya Hai Tumne Jo Dil Ko (Saregama CD release) at least bringing out the sparkle in Asha Bhosle’s voice, though we can still see the recording straining to accommodate the violin. Luckily, we had RD Burman’s 1942 A Love Story in the 1990s, giving us his genius with wonderful clarity. Pyar Hua Chupke Se has a lovely violin intro, leading into the sound of tinkling bells, followed by an orchestral passage with the sitar, a male chorus, and strings. Exquisite.

We can see further improvement in the 80s. A truly miraculous recording, now very popular as an LP with audiophiles in India, is the soundtrack of Silsila. The music is composed by maestros Shiv Kumar Sharma and Hariprasad Chaurasia, and though their later work is not recorded as pristinely, this album is spectacular. Yeh Kahan aa Gaye hum starts with Amitabh Bachchan’s legendary baritone, and the voice is clear, deep and resonant. Dekha Ek Khwab has Kishore and Lata in the best recording of their voices I have heard. Ironically, a later album, Khayyam’s Umrao Jaan, is not as well recorded. But it does give us the soulful sarangi passage in In Aankhon Ki Masti, and we can start to hear the magical sounds of the tabla, easily the most intricate and versatile of percussion instruments, more clearly.

It is the 90s that start to yield top-notch recordings. We have AR Rahman, especially when he was working with the legendary sound engineer H. Sridhar (one of the joys of audiophilia—apart from discovering new instruments—is the joy of encountering and acknowledging the genius of sound engineers: H. Sridhar deserves to be linked to Rahman in the way George Martin is remembered as the fifth Beatle). The bass line of Dil Se Re is a revelation, as is a quiet electronic ‘UFO’ hum that travels from left channel to right channel in Chaiyya Chaiyya, starting at 0:43 and running into Sukhwinder’s opening lines. Jeeya Jale has terrific instrumental music, weaving in the mridangam and the ghatam. Rahman is a great Bollywood choice to get the most out of good audio equipment.

Musician AR Rahman performs during the International Indian Film Academy Rocks show in 2017. Reuters

Gully Boy provides an opportunity to hear the difference between mixes. We can listen to and compare Divine’s original single with the film version. The difference is particularly noticeable when the bass kicks in at around the 0: 40-second mark (a warning: the differences are a bit muted in the YouTube versions of the two tracks because YouTube’s quality is lower). You’ll notice that the film version has pushed the vocals back, so they seem to sit under the bass line. In the original, the vocals are more ‘forward’, more clearly audible over the bass track. The film version’s bass is fuller-bodied, having a deeper, more resonant sound, while remaining tight. The single’s bass is both more shallow and seems to spread. I prefer the original single to Ranveer Singh’s take musically, but, in many respects, the film’s recording is better.

Exquisite recordings of Indian Classical Music

Indian classical music fared better because of its international profile. The genius of our classical tradition was acknowledged far and wide, and attracted the best recording equipment and talent to itself. Even a 1955 recording of sarod maestro Padmavibhushan Ustad Ali Akbar Khan—the very first to feature a full 20-minute exposition of a raga, and the first Indian Classical music to appear on a 33 1/3 rpm album—has soulful clarity. Chatur Lal’s tabla shines in the recording. You can hear the Ustad in 1955 in Ammp Records’s Ali Akbar Khan: Then and Now.

But to touch an audiophile pinnacle, you should listen to Indian Architexture, an album released by the small American record label Water Lily Acoustics (WLA). WLA has a big library of exquisite recordings. In Architexture, the main strings of the Ustad’s sarod are clear and resonant, and you can almost separate the chikari strings, played together, that provide the rhythmic accents to his magical playing. Swapan Chaudhari’s tabla is the best recorded and represented I have heard, each beat retaining its character.

A bit of audiophile vocabulary is good to introduce here. The way a musical sound first hits us is called its ‘attack’. One wants the attack to be identifiably separate, and precise: a sharp stab of sound. The way the note dies is called the ‘decay’. Every note goes through a journey, starting from something clear and spreading or breaking. Think of the sound of cymbals in a drum set (or listen here). When the drummer hits the cymbal with his stick, there is the first ‘t’ sound, the hard, quick sound of wood hitting metal. This is the attack. Then there is the lingering hissing sound of the cymbal vibrating. This is the decay.

In a good recording, and over good equipment, one expects to hear the attack clearly, and then take in the lingering aftereffects. These aftereffects, too, need to be clear and characteristic. It is possible to have, instead, a ‘diffuse’, spreading sound, where the attack and the decay blend in messily and even crowd out the next note.

As one can imagine, this is just the humblest of introductions. The journey of the audiophile is one of almost daily discovery. And these discoveries are hardly made in isolation—I’ve discovered most of these tracks with the help of friends and strangers who are part of the community. To find companions on this journey, I recommend joining The Indian Audiophile Forum on Facebook, which has an active and helpful community (just make sure to search the forum first for information before asking questions that have been asked before).

On Formats, DACs and amps

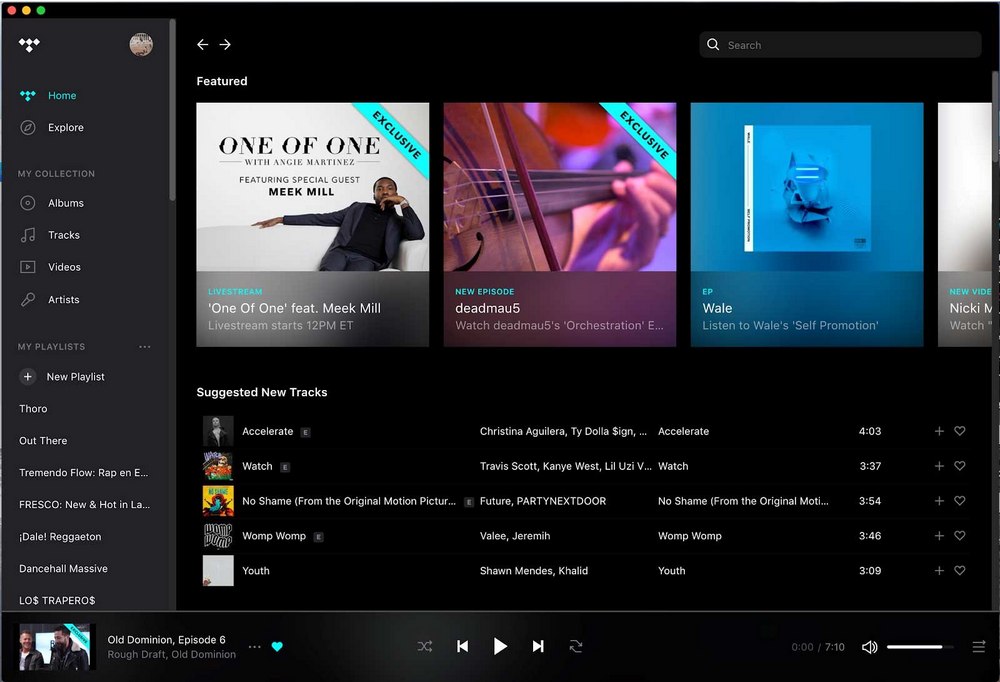

Once we have a good recording, we have to consider the format in which it is digitised. At more advanced levels of expertise and expenditure, the battle between FLAC and AAC and OGG can become a bloodsport. Some would say that Audio CD quality is the bare minimum, but for beginner audiophiles, in my opinion, even a 320 kbps MP3 makes enough of a difference to get started. As you go along on your journey, you can make the extra effort to source higher quality recordings, like using a VPN to access Tidal, which provides high-fidelity audio streaming for a premium price.

Tidal is a subscription-based music, podcast and video streaming service that lets you download lossless audio files. Image: Tidal

Typically, you will use your smartphone or your laptop to play a digital file. Each of our devices that play music actually have yet another key component, something that converts digital information, the bits and bytes of our music files, into analog electric signals that can be converted into sound by our speakers and headphones. The component that does this job of digital to analog conversion can be compared to the graphics card in your computer: there can be a marked difference in performance based on how good that component is.

Unfortunately, there is hardly any laptop or smartphone that has a good enough digital-to-analog converter (DAC). LG has used a high-quality DAC in its V20 and V30 models, but I doubt anyone reading this article will buy a smartphone just for its audio performance. Besides, there are external DACs now that provide better performance and convenience at a low cost.

DACs, and another component, amps, which boost and smoothen electric signals, can both make a telling difference in a good headphone.

Beginner audiophiles, however, should wait to discover the benefits of these later — the first thing to acquire is a good set of headphones. You’ll get more out of your music immediately with these. The difference will be substantial, even revolutionary, even if you’re just using a smartphone or a laptop to play your music. Both you and anyone around you who listens to a good pair of headphones, even without changing anything else, will be able to tell the difference.

Tech2 is now on WhatsApp. For all the buzz on the latest tech and science, sign up for our WhatsApp services. Just go to Tech2.com/Whatsapp and hit the Subscribe button.

Post a Comment