The New York TimesJan 26, 2021 12:56:49 IST

In desperate times, there are many ways to stretch vaccines and speed up inoculation campaigns, according to experts who have done it.

Splitting doses, delaying second shots, injecting into the skin instead of the muscle and employing roving vaccination teams have all saved lives — when the circumstances were right.

During cholera outbreaks in war zones, Doctors Without Borders has even used “takeaway” vaccination, in which the recipient is given the first dose on the spot and handed the second to self-administer later.

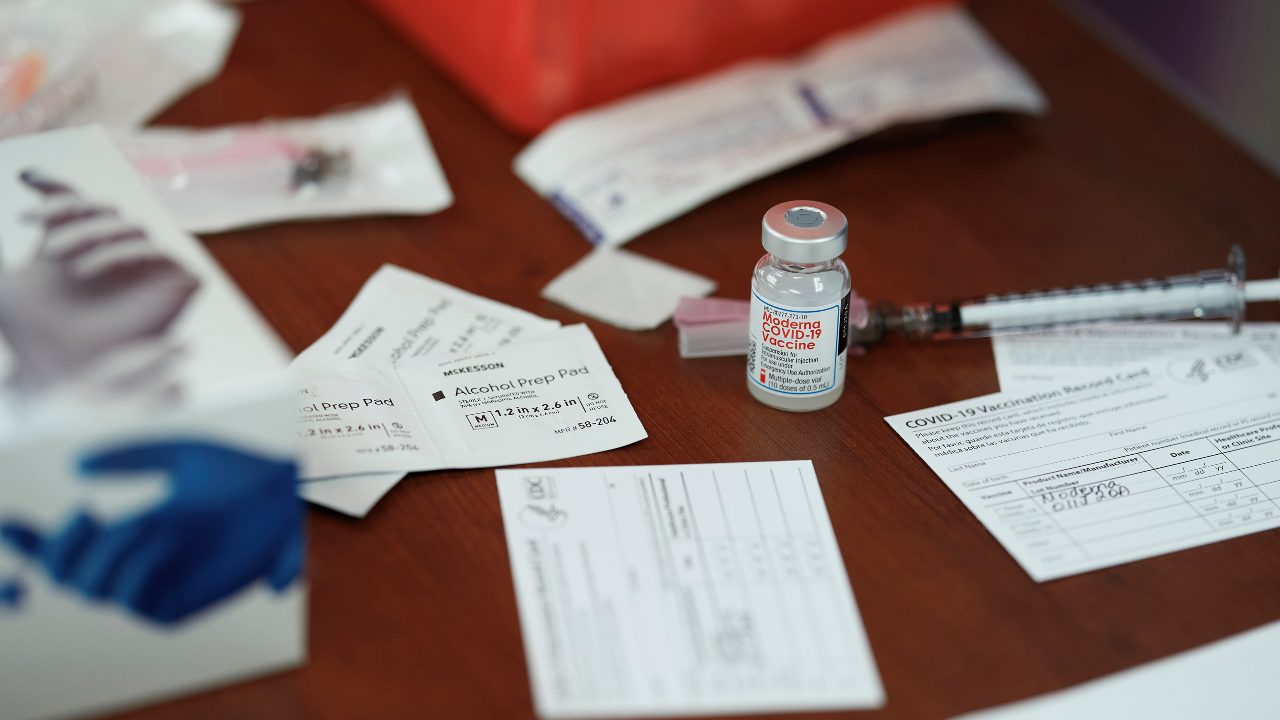

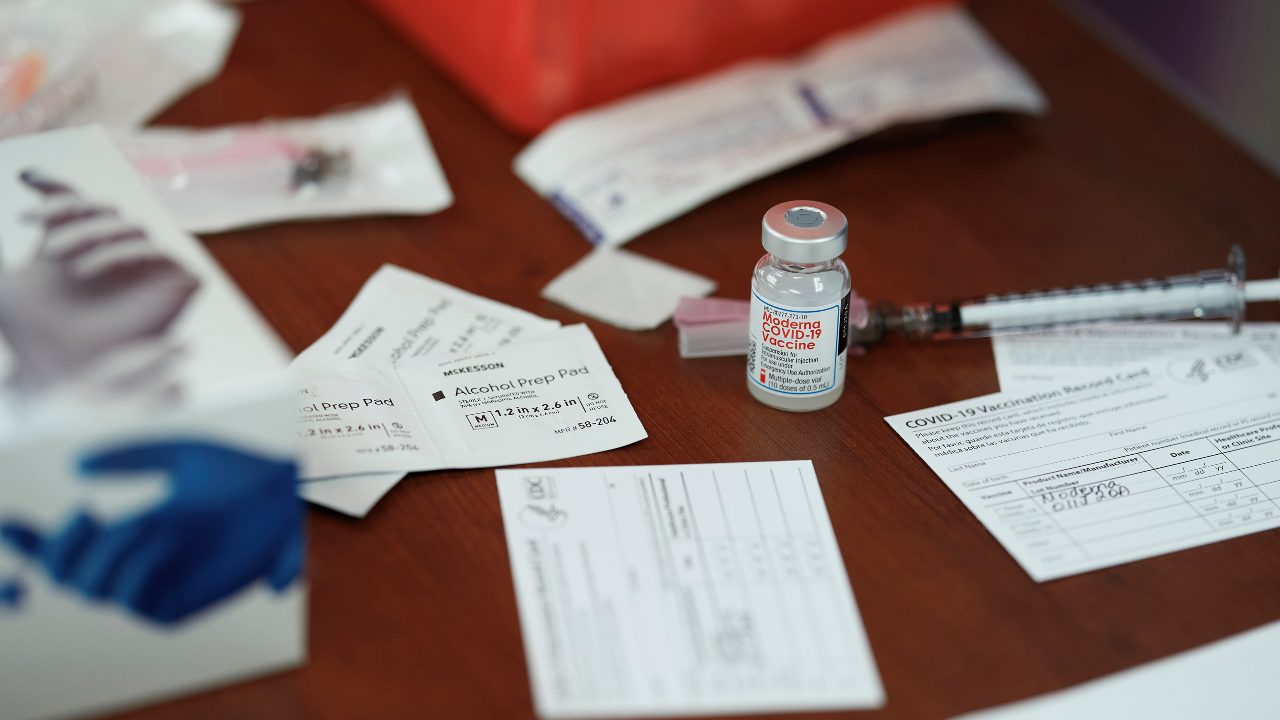

A vial of Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccine in Mount Pleasant, Texas, on Dec. 21, 2020. Shortages of shots for yellow fever, polio and other diseases have led to innovative solutions even in very poor countries. (Cooper Neill/The New York Times)

Unfortunately, experts said, it would be difficult to try most of those techniques in the United States right now, even though vaccines against the coronavirus are rolling out far more slowly than had been hoped.

These novel strategies have worked with vaccines against yellow fever, polio, measles, cholera and Ebola; most of those vaccines were invented decades ago or are easier to administer because they are oral or can be stored in a typical refrigerator.

The new mRNA-based coronavirus vaccines approved thus far are too fragile, experts said, and too little is known about how much immunity they confer.

The incoming Biden administration should focus on speeding up production of more robust vaccines “rather than playing card tricks” with current ones, said Dr Peter J. Hotez, dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston and the inventor of a coronavirus vaccine.

There are two strategies that might work with the current vaccines, but each is controversial.

The first is being tried in Britain. In December, faced with shortages and an explosive outbreak, the country’s chief medical officers said they would roll out all of the vaccines they had, giving modest protection to as many Britons as possible. Second doses, they said, would be delayed by up to 12 weeks and might be of a different vaccine.

There is some evidence for the idea: Early data from the first 600,000 injections in Israel suggest that even one dose of the Pfizer vaccine cut the risk of infection by about 50 percent.

Nonetheless, some British virus experts were outraged, saying single doses could lead to vaccine-resistant strains. The Food and Drug Administration and many U.S. vaccinologists also oppose the idea.

Moncef Slaoui, the chief scientific adviser to Operation Warp Speed, raised a different objection to the British plan. Single doses, he warned, might inadequately “prime” the immune system; then, if those vaccine recipients were later infected, some might do worse than if they had not been vaccinated at all.

He recalled a 1960s incident in which a weak new vaccine against the respiratory syncytial virus, a cause of childhood pneumonia, backfired. Some children who received it and later became infected fell sicker than unvaccinated children, and two toddlers died.

“It may be only 1 in 1,000 who get inadequate priming, but it’s a concern,” Slaoui said. As an alternative — the second strategy for stretching the vaccines — he proposed using half-doses of the Moderna vaccine.

There is strong evidence for doing that, he said in a telephone interview. During Moderna’s early trials, the 50-microgram vaccine dose produced an immune response virtually identical to the 100-microgram one.

Moderna chose the higher dose as its standard partly to be extra sure it would work; company scientists at the time had no idea that their product would prove 95 percent effective. The higher dose would also have a longer shelf life.

But the vaccine works better than expected, and shelf life is not an issue, so Slaoui suggested using the lower dose.

“The beauty is, you inject half and get the identical immune response,” he said. “We hope that, in a pandemic situation, the FDA may simply accept it rather than asking for a new trial.”

Many experts disagreed with the idea, including Dr Walter Orenstein, associate director of the Emory Vaccine Center in Atlanta. “We need to know more before we can feel comfortable doing that,” he said.

“Let’s stick to the science,” added Dr Paul Offit, director of the Vaccine Education Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. “There are no efficacy data on a partial dose.”

Although like Slaoui, Offit opposed delaying second doses, he expressed doubt that doing so, as the British have, would raise the risk of worse outcomes in the partially vaccinated.

Trials in which monkeys or other animals were vaccinated and then “challenged” with a deliberate infection did not cause enhanced disease, he noted. Also, the four coronaviruses that cause common colds do not cause worse disease when people get them again. And people who have COVID-19 do not get worse when they receive antibody treatments; generally, they get better.

When Less Is More

As is often the case, experts disagree about how and what a new vaccine will do. Some point to hard evidence that both fractional doses and delayed doses have worked when doctors have tried them out of desperation.

For example, yellow fever outbreaks in Brazil and the Congo have been stymied by campaigns using as little as 20 percent of a dose.

One shot of yellow fever vaccine, invented in the 1930s, gives lifelong protection. But a one-fifth dose can protect for a year or more, said Miriam Alia, a vaccination expert for Doctors Without Borders.

In 2018, almost 25 million Brazilians, including those in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, faced a fast-moving outbreak at a time when there were fewer than 6 million shots in the global supply. The Brazilian government switched to one-fifth doses and sent mobile teams into the slums urging everyone they met to take them, and filling out minimal paperwork. It worked: By 2019, the threat had faded.

The tactic has also been used against polio. Since 2016, there has been a global shortage of the injectable polio vaccine, which many countries use in conjunction with the live oral one. The World Health Organization has overseen trials of different ways to stretch existing supplies.

India first tried half-doses, said Deepak Kapur, chair of Rotary International’s polio eradication efforts in that country. Later studies showed that it was possible to drop to as low as one-fifth of a dose as long as it was injected just under the skin rather than into the muscle, said Dr. Tunji Funsho, chief of polio eradication for Rotary International’s Nigeria chapter.

“That way, one vial for 10 can reach 50 people,” Funsho said.

Skin injections work better than muscle ones because the skin contains far more cells that recognize invaders and because sub-skin layers drain into lymph nodes, which are part of the immune system, said Mark Prausnitz, a bioengineer at Georgia Tech who specializes in intradermal injection techniques.

“The skin is our interface with the outside world,” Prausnitz said. “It’s where the body expects to find pathogens.”

Intradermal injection is used for vaccines against rabies and tuberculosis. Ten years ago, Sanofi introduced an intradermal flu vaccine, “but the public didn’t accept it,” Prausnitz said.

Intradermal injection has disadvantages, however. It takes more training to do correctly. Injectors with needle-angling devices, super-short needles or arrays of multiple needles exist, Prausnitz said, but are uncommon. Ultimately, he favours microneedle patches infused with dissolving vaccine.

“It would really be beneficial if we could just mail these to people’s homes and let them do it themselves,” he said.

A bigger disadvantage, Slaoui, is that intradermal injection produces strong immune reactions. These can be painful and can bleed a bit and then scab over and leave a scar, as smallpox injections often did before the United States abandoned them in 1972.

The lipid nanoparticles in the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines would be particularly prone to that effect, he said.

“It’s not dangerous,” he added. “But it’s not appealing and not practical.”

Boots on the Ground

What the United States can and must do now, health experts said, is train more vaccinators, coordinate everyone delivering shots and get better at logistics.

Thanks to battles against polio, measles and Ebola, some of the world’s poorest countries routinely do better vaccination drives than the United States is now managing to do, said Emily Bancroft, president of Village Reach, a logistics and communications contractor working in Mozambique, Malawi and the Democratic Republic of Congo and also assisting Seattle’s coronavirus vaccine drive.

“You need an army of vaccinators, people who know how to run campaigns, detailed micro plans and good data tracking,” she said. “Hospitals here don’t even know what they have on their shelves. For routine immunization, getting information once a month is OK. In an epidemic, it’s not OK.”

In 2017, the United Nations Children’s Fund recruited 190,000 vaccinators to give polio vaccines to 116 million children in one week. In the same year, Nigeria injected measles vaccine into almost 5 million children in a week.

In rural Africa, community health workers with little formal education delivered injectable contraceptives like Depo-Provera. The basics can be taught in one to three days, Bancroft said.

Training can be done on “injection pads” that resemble human arms. And data collection must be set up so that every team can report on a cellphone and it all flows to a national dashboard, as happens now in the poorest countries.

“The U.S. will get there,” Bancroft said. “Practice makes perfect. But the rockiness we’re seeing now is the lack of experience.”

Donald G. McNeil Jr. c.2021 The New York Times Company