Many experts outlined that big investments in trials and vaccine development need to be accompanied by big investments in science.

The Indian Council of Medical Research hosted an international symposium on 30 July, bringing global health and vaccine experts under one (virtual) roof to discuss science & ethics around COVID-19 vaccines. Over 25 global experts discussed issues around the speed, safety & fairness in development & deployment of coronavirus vaccines.

The event kicked off with brief insights about the fight against COVID-19 pandemic Professor K Vijaya Raghavan, Principal Scientific Advisor to Govt of India; Dr Renu Swarup, Secretary of the Department of Biotechnology; Prof Heidi Larson, Director of The Vaccine Confidence Project; and Dr Adam Kamradt-Scott, Director of Global Health Security Network.

India’s strength in the vaccine race – manufacturing

“India stands together to realize the shared mission of developing a vaccine for COVID-19,” said Dr Raghavan. “Our scientists and engineers are committed to bringing out working vaccines for India and the world using ethical, fair and fast means.”

India has a large manufacturing capability for vaccines, with a foray of biotech companies and vaccine makers. The country has also entered into partnerships with alliances to ensure equitable distribution of those vaccines, experts said.

“Numerous vaccine developers are coming forward in research collaborations with Indian and international partners,” Dr Renu Swarup said. “Our collaborations with both GAVI and WHO will enable not just development, but also equitable distribution of a working vaccine from India.”

Dr Anthony Fauci, top infectious diseases expert in the US, said that India’s private sector has an important role to play. As working vaccines get approval from clinical trials, the manufacturing capacity of Indian vaccine makers will be very useful in meeting the capacity for global vaccine distribution, he added.

Asked if human challenge studies were needed to expedite the vaccine testing process, Fauci said it was “not necessary” at this point.

“The full impact of a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine is not very well understood…so infecting healthy people with COVID-19 is not ethically or scientifically called for at this point in time,” he explained. Though many experts explained the advantages of carrying our challenge trial in volunteers.

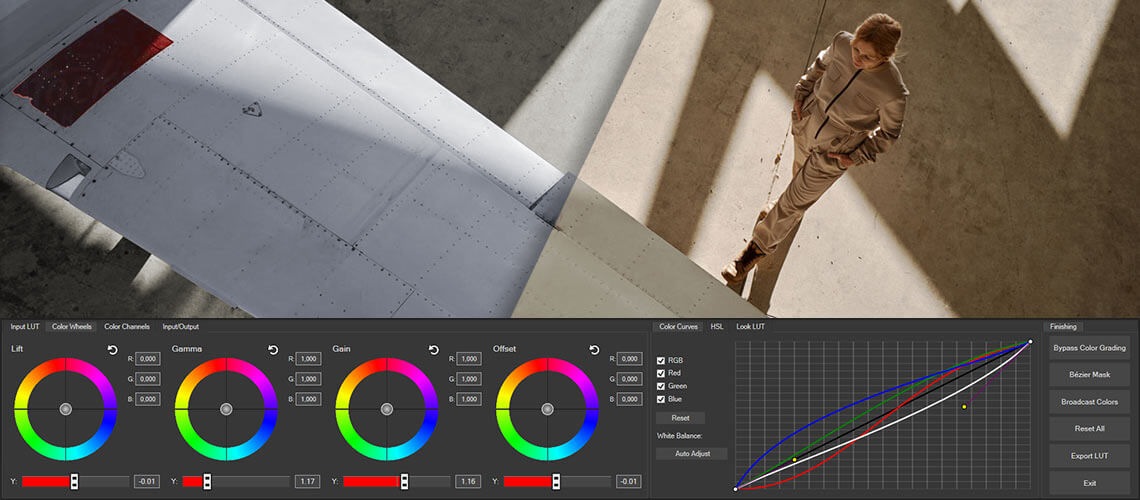

The J&J vaccine, which enters Phase 2 trials in late-July after successfully protecting monkeys from COVID with a single shot. Image: JnJ

Some experts argued for human challenge trials

Clinical trials currently not being conducting as human challenge trials for a COVID-19 vaccine, which involved deliberate infection of volunteers to make sure the vaccine is a working preventive.

Dr Gagandeep Kang, who is due to retire as executive director of the Translational Health Science and Technology Institute in August, said that human challenge trials have not been conducted in India so far, but the government has been discussing the surrounding ethics.

They are a particularly important dialogue for India, Kang said, even outside COVID-19 since the country is home to a range of endemic diseases, which are particularly and consistently affect the population. Challenge trials are considered powerful tools in preparing for outbreaks of emerging and endemic infections.

Professor Nir Eyal, Director of the Center for Population-Level Bioethics (CPLB) at Rutgers University, was among those who argued that challenge trials were ethical. If the risk of human challenge trials for COVID-19 vaccines were minimized and communicated clearly, they can be ethical, he said.

“It can be ethical in the same way that we accept medical volunteers or kidney donations….it is only a request, with very high-quality informed consent. The volunteers will be given detailed demonstrations of the various side effects they may encounter in the future,” Eyal said.

Moreover, public health systems could benefit from having human challenge trial data. Eyal said that this data could help outline some level of regulation even on private vaccine makers where distribution is concerned.

Prof Marc Lipsitch, epidemiologist and Director of the Center for Communicable Disease Dynamics at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, added that challenge trials can help experts and policymakers build strategies around distribution.

“Challenge trials may play an important role in making decisions about distribution,” Lipsitch said. “It may involve essential workers, high-risk population, and coronavirus transmitters, who will be most likely to receive the earliest doses.”

Other benefits for developing nations, which may not be leading the global vaccine race, are the ability of challenge trials to speed up their research, Lipsitch said, adding that it prevent them being at the mercy of “bully countries” to get enough vaccine doses for its citizens.

Considerations for vaccine distribution in India

Another topic of discussion at the symposium was equitable distribution of working vaccines, with the authority of the World Heath Organization undermined, and its power challenged by the United States.

“The rollout of a vaccine requires community acceptance, which is an important consideration that is often lost in discussion of equity,” said Dr Poonam Singh, Regional Director of WHO in South East Asia. “Vaccines need to be considered a common good, and WHO is supporting equitable access with the COVAX and ACT-Accelerator programs.”

Secretary of India’s Ministry Health and Family Welfare Rajesh Bhushan, also outline some national challenges that are both a medical and ethical concern to address before a COVID-19 vaccine is distributed. Apart from the wide range of comorbid conditions in the Indian population, the pandemic has also affected people across socioeconomic divides, he said.

“A big percentage of the severely affected are malnourished…and people with weak immune systems from long-term poverty,” Bhushan added.

Where there are fewer healthcare workers than people with ill-health in developing public health systems like India, different systems for vaccine distribution could be effective, experts suggested. For instance, the allocation of vaccine doses per capita instead of doses per health care worker might be more suited to the needs of developing nations.

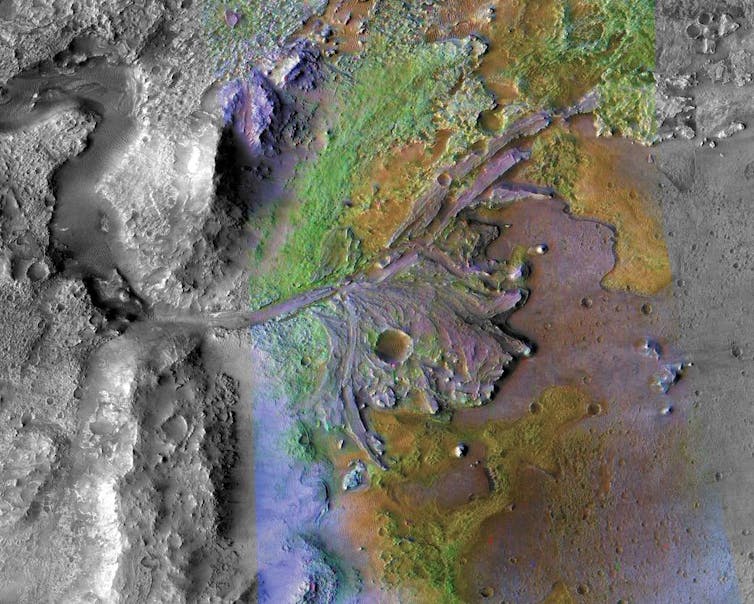

Older people remain most at risk of death, but there are many conditions that inflame COVID-19. Image: AP

Safety, efficacy cannot be compromised

Many experts outlined that the big investments being pumped into clinical trials and vaccine development need to be accompanied by big investments in science. So cutting corners where safety and efficacy of a vaccine are concerned is simply not an option.

“We can accelerate the funding and the bureaucratic elements of the vaccine trials, but the scientific method and randomized controlled trials cannot be accelerated,” Professor Peter Piot, Director of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, who himself had been recovering from COVID-19 for 2 months.

The study of safety and efficacy extend well beyond the Phase 3 trials. An equally important safety test comes after the vaccine is released to the masses, and the number of incident after this roll out is documented carefully.

“Priorities will need to be made as to which groups will received the vaccine first, considering the doses will be limited,” Walter Orenstein, Director of Emory Vaccine Policy and Development and former director of the US National Immunization Program.

This will likely be done based on how likely it is for a certain group to contract COVID-19, like healthcare workers who are most at risk. Also considered are people with health risks, like old age and comorbid conditions, which are more likely to trigger side effects, Orenstein said.

The matter of “preparedness”

Addressing how countries can be better prepared for future epidemics and pandemics, experts spoke of how models to predict such cases are not always reliable.

“We predicted that a different wave of something like a second SARS virus will come around many years ago, but we didn’t foresee that it would be this widespread,” Professor Adrian Hill, Director of the Jenner Institute and Professor of Human Genetics at the University of Oxford.

Experts agreed that while the coronavirus pandemic has undoubtedly given rise to new ideas and experiences with pandemic modelling, statistics and data alone cannot be used as the primary tool for pandemic preparedness.

Instead, a mix of building resources pre-emptively and making horizon predictions for what could likely be the next epidemic to surface is a better strategy, Prof Hill said.